On cursive's decline & the pleasures of braided armpit hairs

Or: I think the kids are all right.

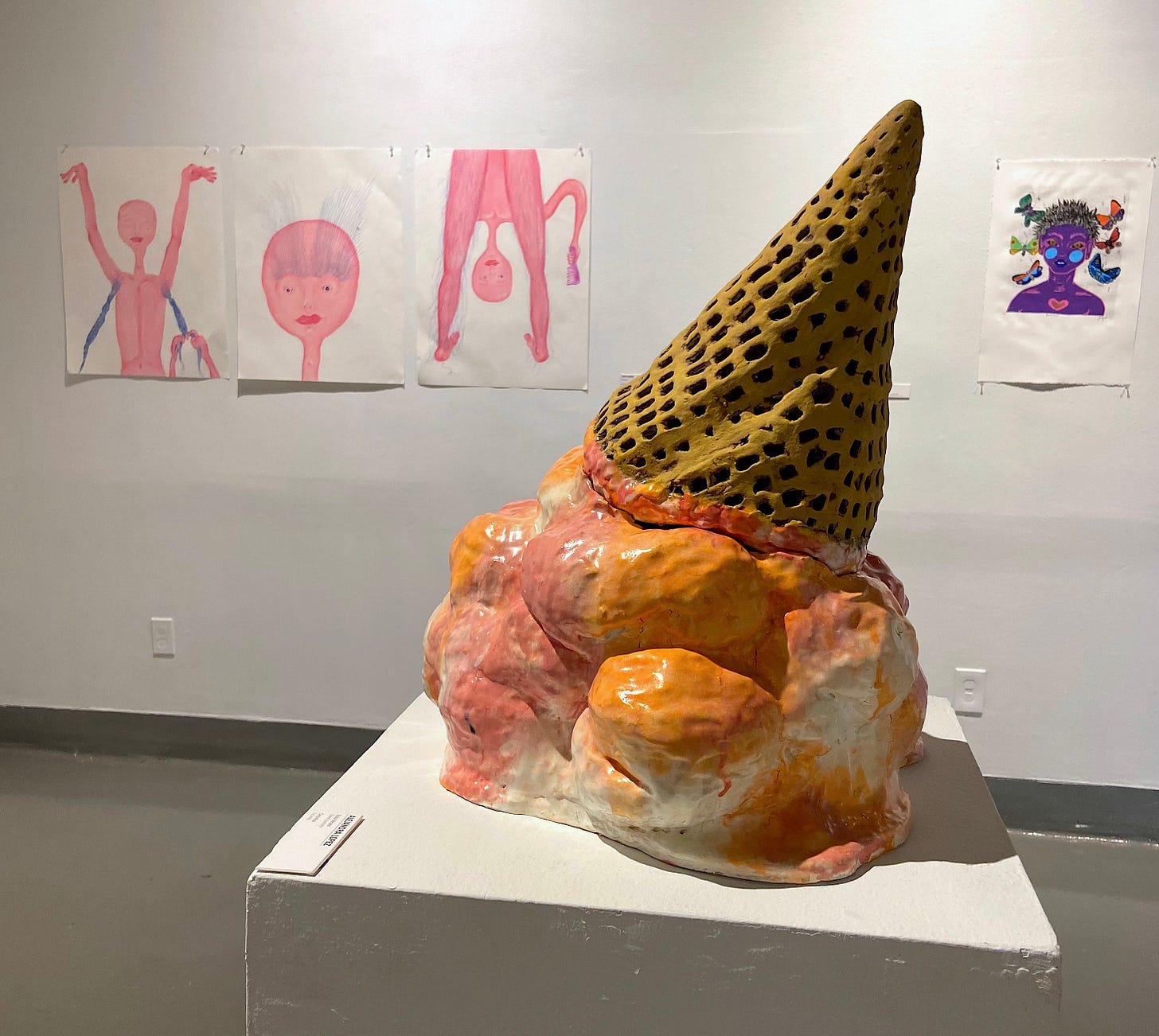

Last week, an exhibition of student work opened at the university art center where I work. With hundreds of works of art in a range of media—painting, drawing, sculpture, ceramic, video, photography, and graphic design—the show was a bear to install, a challenge to find visual relationships across such diverse projects, styles, and materials. It’s a crowded, salon-style hang and, while I see the relationships we tried to draw out across works, the show as a whole reads like a jumbled room full of young people surveying a terrible time and trying to hold it together. Which is exactly what it is.

In one corner, a row of three drawings of a pink, bald figure has long strands of blue armpit hair, leg hair, and eyebrows, confounding the figure’s efforts to tame them. The work is silly but somehow also gets at the strange slippages that happen during pandemic years. What expectations are abandoned, transformed, what rituals are stoppered when the world becomes unhinged from its more familiar rhythms? The figure peers down between her ankles, a hair brush in hand, as she tries to comb the unruly hairs sprouting from her legs. Another set of hands assists her in braiding the hair that sprouts from her armpits as she lifts her arms overhead and closes her eyes in contentment.

I wonder what it must feel like to be completing an art degree this year, after more than two years of pandemic experience. To be 20 or 21 and trying to develop your creative work alongside such crushing losses is either an act of self-preservation or a deeply optimistic decision. Maybe both.

In a nearby gallery, a small charcoal composition from a life drawing class depicts a nude female figure, leaning across the page in a simple contrapposto. She is the first figure drawing I have seen who is wearing a mask, and I find its inclusion unsettling, particularly because of how unremarkable it seems.

Nearby, three gorgeous still life paintings of vegetables on small cardboard panels are extraordinarily precise in their rendering. The vegetables are rotting.

I visited an artist’s studio last week in El Paso. She makes drawings and collages, in some cases precisely rendered detail drawings, and in other cases, simple compositions of found things, perhaps with a scrap of a sentence to accompany a line or a shadow. In a series of drawings, she draws an expansive sky: the reference is from a photograph she took and the sky is a local one, the way a Texas sky is uniquely endless. There’s something, she tells me, about skies lately. They are appearing in her students’ work and in hers. Maybe, we think together, there is something about this sky that allows you to look away and find respite. To focus elsewhere, to imagine something otherwise.

What do you look at, or what do you look away from, when you work?

These are the last few days of the academic year and, while I work at a university, I don’t currently teach at that university, so my end of year stressors are quieter than those of the over-extended faculty around me. And yet, still, I was surprised last week at a faculty women’s brunch, to hear professors doubling-down on their frustrations that students no longer know how to write in cursive or how to spell. They were complaining about term papers written on cell phones and colloquial usages of words entering art history essays. Their complaints felt strange and alien, a weirdly recalcitrant elitism that seemed like a fixation, out of place, particularly here on the border and now. The Supreme Court memo draft predicting the overturn of Roe v. Wade had just been leaked and I am certain that cursive hand writing and studied orthography will not ensure that the young women they teach will get the health care they need in this wickedly, endlessly unfolding U.S. of America, but also maybe that is too much to bear. Handwriting and its decline is, I guess, a more innocuous sign of the end-times, something easier to describe while we shake our sticks at the sky.

What do we look at and from what do we look away?

I may have mentioned that I am setting up a ceramics studio in an old adobe building behind my house. Or, actually, that is a lie. Something closer to the truth is that I have a wheel that is sitting in a darkened and dusty room, surrounded by boxes, waiting for me to make time to set up my studio. I haven’t had my hands in clay in several months. It has felt good to start finding my footing in this new work environment and to begin to imagine exhibitions again; it has felt good to spend time with college students, many of whom were born the same year I held my first museum internship in graduate school. Installing this student exhibition gave me time to see the hundreds of experiments and explorations that young people on the border have been making while also dealing with profound ruptures and heavy layers of grief. They remind me that I need to set up this studio for tomorrow, return to my wheel, get my hands dirty, and try making a thing, even if I’m not sure how to make anything new or what to do with the news of the day. I guess newness isn’t really the point: it’s more the intentional looking that matters, the intentional engagement, the present-ness of making something, the insistence on play.

At my new job, I’ve made a friend and we talk often about writing (she is trying to unlearn some painful grad school writing methods). Like teaching, writing is one of those places where I am unsure what I am going to learn, and yet it is one of the most important spaces I’ve found for working through ideas. The studio is another of those places, full of possibility in its particular lexicons, its wordless intimacies with materials, and how materials move through ideas, through feelings, through the world. I think about cursive becoming a dead language, and yet I love that the younger people around me are building new languages, finding the cadences and rhythms and ironies and abbreviations and emojis that give texture to what they want to say when old forms fail them. Sometimes the words that exist already don’t get it right. Sometimes pretty ways of writing are just absolutely hollow.

When I feel slow and heavy, when the world feels so dedicated to our wildly inventive inhumanity, I think of that pink figure’s acceptance and wonder, her own body new and strange. Or, maybe what this exhibition last week reminded me is that, even though nothing is all right, the world is so hard, and my studio is shuttered, well, maybe the kids are going to be all right.

Laura August, PhD makes essays and exhibitions, lumpy pots and wild gardens. She has curated more than 20 exhibitions as an independent curator working between the U.S. and Central America. In 2021, she was named an inaugural Mellon Arts + Practitioner Fellow at the Yale Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity, and Transnational Migration, and her writing about contemporary art in Guatemala City has been recognized with an Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant. Alongside her consulting practice for artists and writers, she teaches a process, practice, and professional strategies class for artists at the Glassell School of Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. She currently makes her home on the edge of the Chihuahua Desert, and she is Curator at the Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts at The University of Texas at El Paso.