On Russian short stories, criticism, and how art won't heal us... (but gardens might?)

In which I read A Swim in a Pond in the Rain after a road trip across Texas and have some thoughts (and lots of digressions in italics)

When I was a teenager, I spent a few years being fascinated with Russia. This means: I did little to no research, but I had some very fast-and-loose ideas of Russia as a place, based on a few excerpts of 19th century literature and a few maps. I was curious about how that place helped me to understand the strangeness of my own place: a small college town in rural Georgia, home to one of the world’s largest mental health asylums, Flannery O’Connor, and the state penitentiary. I read Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment my junior year, and then wrote several impassioned but unsuccessful college essays about what I would do if I was Roskolnikov. In hindsight, I can see why colleges would be wary of an applicant who imagined herself in the shoes of this particular character. But, at the time, I thought his moral dilemmas were important to parse. And, up to that ripe old age of 17, I had seen nothing like it in literature.

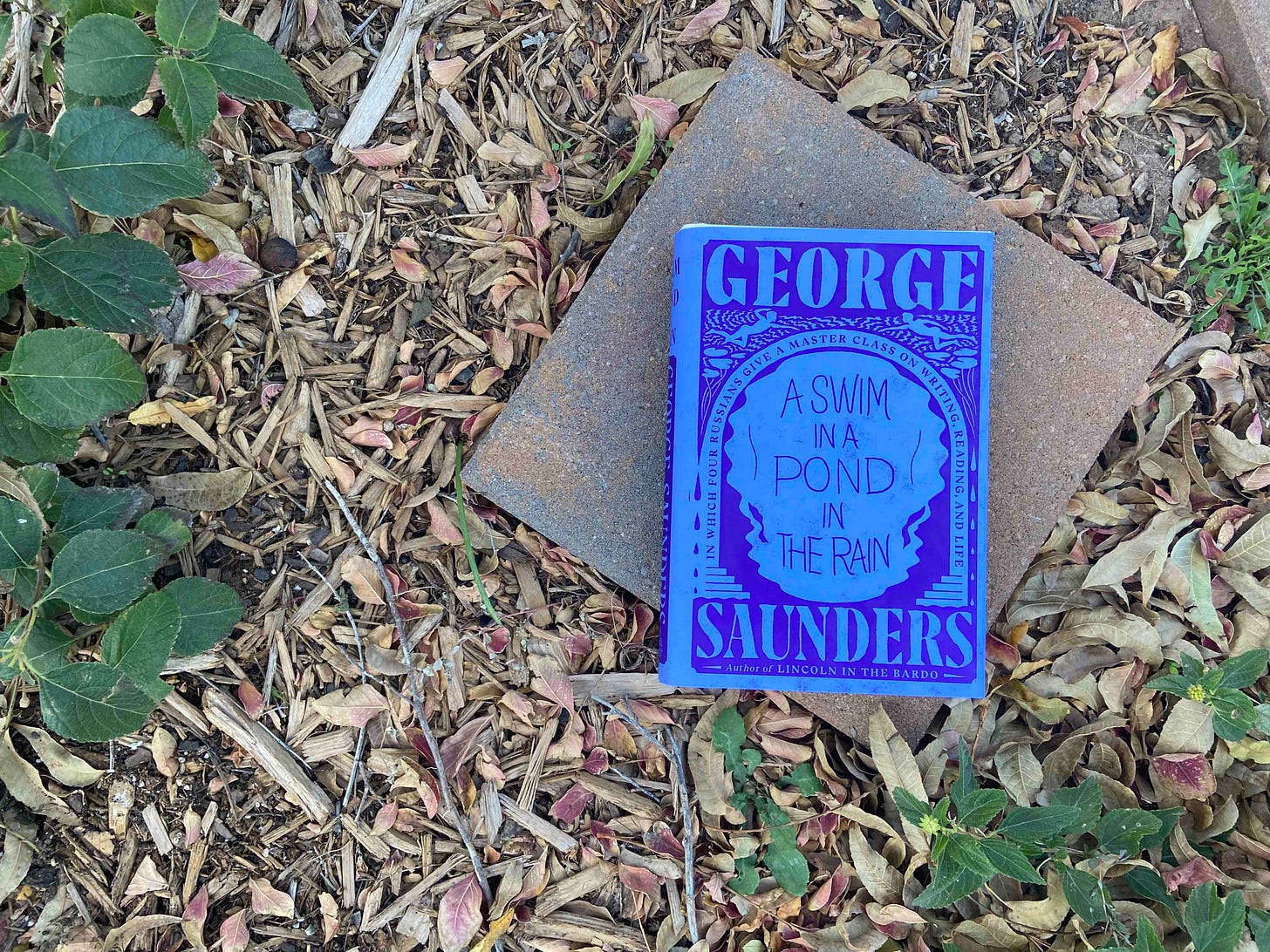

This is a long, nostalgic preamble to say that I have been reading George Saunders’ new book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, in which he includes translations of seven stories by four nineteenth-century authors (Checkhov, Turgenev, Tolstoy, and Gogol), followed by essays thinking about their construction, their many meanings, their characters. It’s a very nerdy and optimistic book, and the teenage me who lives in my heart is giddy with delight. Would I recommend the book to you? Erm, well, maybe? Or maybe start with some of Saunders’s own short stories, perhaps Civilwarland in Bad Decline, and just enjoy the juiciness of his prose and the wild realness of his American imaginings without the didacticism? Or find a book of Russian short stories and heat up some nice tea, find a blanket, and meander through them yourself? Or, if you like wading through craft essays about writing and harbor some nostalgia for 19th century Russian literature, then absolutely yes! You should read this book! It’s marvelous!

So, why am I spending several paragraphs describing my reasons for loving a weird and teacherly book that I don’t necessarily recommend?

In it, Saunders takes his characteristic wit and sensitivity to structure, using both to reframe classic stories and tell us how he reads them. It’s an act of what we might call criticism, if we define criticism as a body of writing about another creative body of work; it stems from his teaching, so we might also think of it as a pedagogical tool. As someone who often writes criticism and thinks a lot about pedagogy, I am invested in the form he has chosen. And, as someone who writes often about art and what it might mean, I regularly wonder why this form still matters when the world is burning (or why I persist in doing it, if it doesn’t matter).

In particular, I am interested in Saunders’ conclusion, in which he talks about the kinds of laudatory language we use for the importance of fiction (and, by extension, the arts). “There’s a certain way of talking about stories that treats them as a kind of salvation, the answer to every problem; they are ‘what we live by,’ and so on,” he writes. He agrees, kind of, but then he cautions about the excesses of this kind of talking. Maybe, he adds, “we should keep our expectations humble. We shouldn’t overestimate or unduly glorify what fiction does.”

In April of last year, I was midway through seven weeks of total isolation, living in a friend’s house, alone, in Houston. The city is famous for its medical complex, and I was spending more time than usual near its hospitals, because of where I was staying. Simultaneously, the city’s largest museum was in the final stages of completing its $476-million expansion, which opened later that summer. The incongruity of these two industries—the medical and the arts—sitting side by side in that particular city has never felt more extreme than it did last year. I think it was this extraordinary difference in their functions that made me more sensitive to how unnecessary—at that historical moment—art institutions could be.

Don’t get me wrong: in recent months, my emotional health and mental health have been dramatically improved by visits to exhibitions in museums, galleries, and artist-run spaces, by conversations with artists, by touching things and being (carefully) embraced by their makers. But in April and May of 2020, exhibitions seemed much less urgent to me. In particular, I found myself pushing back against the bumper sticker-style sloganeering about art’s importance that I hear all too often—Art doesn’t heal, I thought, as I watched the news of doctors and nurses battling the pandemic with insufficient supplies in terrifying circumstances. Waving my grumpy stick at the world, I exclaimed we need to be more specific in our language about the arts! And also, medical workers need appropriate PPE, better pay, and more support! Gah!

(At this point, you should notice that my particular nerdy/misanthropic proclivities continue into adulthood, and maybe I should revisit Dostoevsky).

We’re in a different part of our pandemic adjustments to life, now, and I have more space for the idea that art does something significant for us (though I insist that the art-heals-the-world language should be toned down). Honestly, I’ve always believed art does something significant—hello, I’m 20-years into this field, so I better believe it does something for us. But, like Saunders, I want our understanding of what it does for us to be sensitive and complex, not an inexact panacea for, well—gestures broadly at the world.

In the last few pages of his book, Saunders describes what literature can do: “it causes an incremental change in the state of a mind. That’s it. But you know—it really does it. That change is finite but real. And that’s not nothing. It’s not everything, but it’s not nothing.”

I recently drove across Texas, mostly to see art, and had the luxury of seeing Jennifer Ling Datchuk’s exhibition Later, Longer, Fewer at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft (curated by the wonderful Kathryn Hall). I saw Lovie Olivia’s solo show TIGHTROPE at Bill Arning’s space, and I saw Gerardo Rosales’s mural project at the Moody Arts Center at Rice University. I toured Symbiosis, Cindee Klement’s ambitious site-specific landscape activism at Lawndale, with the artist. I went to every venue of the Texas Biennial (and I wrote something about it). I walked through Ruby City in San Antonio for the first time. I spent a long time with the Afro-Atlantic Histories exhibition at the MFAH. I saw my students’ work, on view at the Glassell School of Art. I returned home a slightly different person. I felt the rumblings of new ideas, I felt sensations of re-connection. I felt like a more and better version of myself. That is: I felt all the feelings that remarkable objects and conversations with artists warm in me.

Saunders doesn’t let himself remain on that last sentence’s broadness. He offers another paragraph, pushing himself to be more specific. How exactly do these stories change our minds? “I am reminded that my mind is not the only mind,” he writes (and I nod emphatically, yes!). “I feel an increased confidence in my ability to imagine the experiences of other people and accept these as valid. I feel I exist on a continuum with other people: what is in them is in me and vice versa. My capacity for language is reenergized. My internal language (the language in which I think) gets richer, more specific and adroit. I find myself liking the world more, taking more loving notice of it… I feel luckier to be here and more aware that someday I won’t be. I feel more aware of the things of the world and more interested in them…” Yes, yes, yes, I nod.

Do you also look closely at exhibitions and projects other artists are making right now and find proposals about connection? Do you sink into the exquisite details of the work, looking carefully and deliberately, thinking about structure and concept and form and space and all that good stuff, and find yourself stronger? I hope so.

Art doesn’t have to heal us (even though it might sincerely make us feel something, feel better, make small changes in our bodies and minds).

Art doesn’t have to heal us, because it already does enough. At Symbiosis, Cindee talked to me about her vision for Houston’s urban landscapes, the way she imagines that small changes can tumble into structural re-thinking of how we build our cities. Like Saunders, I tend to shy away from such big claims for art’s role in changing the world. But what Cindee is fighting for isn’t only large-scale environmental change, it’s small-scale adjustments to how we see our urban environments and respond to them. She’s making a case for the impact that incremental change can have on the world. She’s also making a case for looking closely. Art, she believes, can change one mind, then another, then another, in a wild cascade of possibilities that have real bearing on the world. And that is something I choose to believe in. Even, still.

—Laura

Laura August, PhD is a writer and curator, gardener and enthusiastically mediocre beginning potter. She has curated more than 20 exhibitions as an independent curator working between the U.S. and Central America. In 2017, she received the Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant for her writing about contemporary art, and her essays, reviews, and interviews have been published internationally. Alongside her consulting practice for artists and writers, she teaches a process, practice, and professional strategies class for artists at the Glassell School of Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Yesterday I read “On Russian short stories, criticism, and how art won't heal us... (but gardens might?)” for self-centered reasons 😊. This morning with a clear head, I reread it to learn and dig deeper into my work. I have never thought of art as healing a viewer - so much. However, I can see how it could. From my perspective and conversations with other (primarily middle-aged female) artists, where I see art heal is in the making. Many of my art friends came to art to save themselves. Their making is their therapy from the painful life experiences we humans suffer. I do romanticize the idea that making art can heal the maker and the viewer. And if that does not work-study a garden. Study a garden that supports living organisms above and below ground like you would a complicated contemporary painting layered with modern industrial made and biblical materials, natural history, injustice, community, color, movement, and try to understand the symmetry in contemporary ecological balance and you will change how you see life. And isn’t how we see our mental health.

On Symbiosis- I have spent much of my life fearing failure and letting that dictate the challenges I take on. Now in my mid-60s, I know this is my last chance to see what I can achieve. I also know that the only way to find one's limits is to test them. I alone can not change the ecological path our civilization is on. But if my ideas touch one other person and that one person tells two people, and each tells two people, “We” can heal our planet. I believe in the people of Houston. Thank you Laura, your newsletter just told more than two people. Humans can be amazingly human. Tell two