Hello, you.

I’ve been swimming against currents of guilt and shame for missing some of our weekly appointments in the past month or two. I want to write to you every day, and yet March was a period of intense transition, far beyond what I expected. My work life has required every ounce of my energy in these weeks, as I learn a new commute, new computer systems, and face endless piles of administrative tasks to finalize my appointment. Words have become harder and harder to find as my brain adjusts to being-with-people again.

But it’s April now and, while I’m not saying I won’t miss a week again, I am starting to find some ground under my feet. Things are beginning to level into regular rhythms and familiarities, and I’m happy to be returning to our regular schedule this week. Thank you for your patience and generous support, even as I’ve gotten a bit behind. In these weeks, I’ve been trying to figure out the best way to actually begin to catch us up a bit, without sending you a pile of emails that feel spammy. Toward that end, I include here some writing, a link to some video, a book recommendation, and a suggestion for a writing (or unwriting) activity in your studio, if you are so inclined. Read through these offerings at your leisure. Write to me. Let me know what you’d like to think about, together.

As always, I am grateful for your reading, for your support, for your interest in receiving these letters in your inbox. We are moving into our sixth month of Studio for Tomorrow, and I am as surprised as anybody that this weekly writing has found such a supportive audience. It’s good to be here. Thank you, for so much.

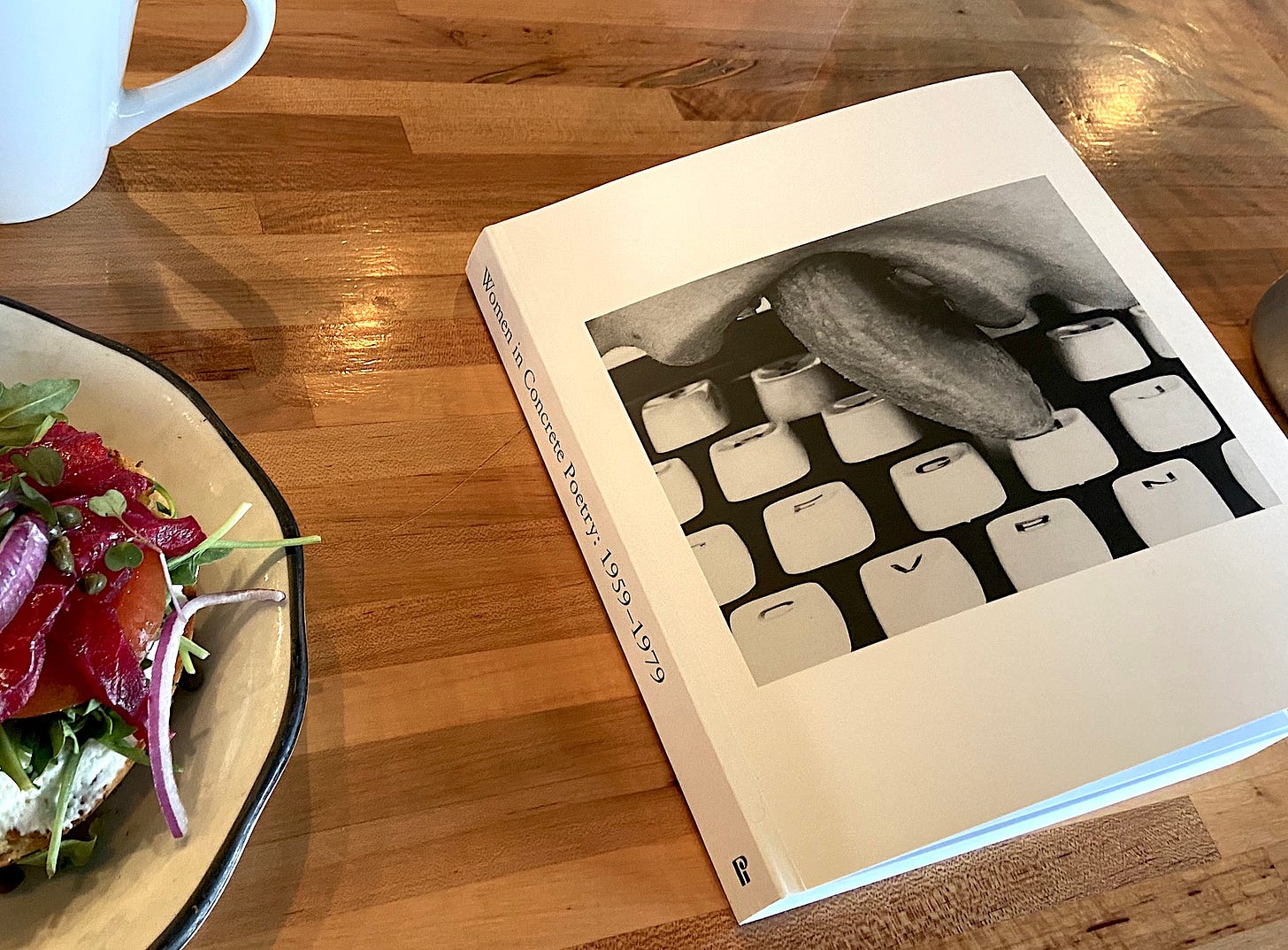

On the cover of Women in Concrete Poetry, 1959-1979, Lenora de Barros’s tongue licks the keys of a typewriter. Or, more precisely, I should say: on the cover of the book, we find a black and white photograph, a work by Brazilian artist Lenora de Barros, an excerpt from a series in which her tongue variously caresses the keys of the keyboard and is stung, caught, and entangled by the hammers inside the machine. The piece, from 1979, is called Poema, and among other things, it might be a helpful metaphor for many artists’ experiences with writing.

Women is a beautiful catalog, published in 2020 (bless any author who published a project that year), edited by Alex Balgiu & Mónica de la Torre. Inside are projects by 50 people who identify as women and who made work that sought out the edges of words themselves, in a rupturous/rapturous relationship with and outside of meaning. Despite their wide variation in geography and background, the writers included share what Mary Ellen Solt describes as concrete poetry’s fundamental requirement: “concentration upon the physical material from which the poem or text is made.”

“Emotions and ideas,” Solt writes, “are not the physical materials of poetry.”

Included are scribbles and drawings, typographic experiments and exploded words. So much repetition: repetition to the point of meaning’s fracture and reassembly; pages of lines and patterns and symbols and photographs of figures inter-spliced into the broken words.

When I began writing this week’s letter to you, I wasn’t sure how to connect concrete poetry to your studio practice. And, I’m not sure any effective connection would stay in the realm of the useful, rather than the treacly. But I’ve been thinking about the materiality of words (always), and the ways that this kind of relationship to writing might coincide with your own diverse practices. What might an artist statement reliant upon textual materiality—words, letters, typographies, sounds of speech, accents, meaning or meaninglessness, formal experimentation, translation—look or sound like?

Italian curator, poet, sculptor, and performance artist Mirella Bentivoglio (cited in the book’s introduction) writes, “Mark-making and handwriting follow the circuits of memory, opening the floodgates to create intriguing maps of the energetic tensions presiding over the formation of thought before it’s crystallized into verbal articulation.”

There is, she continues, a “strangely interwoven rhythm” between “writing-space and sound-time (sound-tempo).”

You can imagine, I hope, the way that writing something parallels the action of making, whether in the application of paint on canvas, the hammer and chiseling of stone or metal into new form, the intricacy of cutting collage into image. Can you imagine, with me, a writing that feels like the movements within dance? Or, what is the movement of a writing?

Several weeks ago, I sent you a few formulas and questions for writing a new artist statement, and many of you reached out to share the results of that project. In the interim, I’ve been thinking a lot about this practice of professionalization (for lack of a better word), and its effects upon creativity. I remain convinced that writing statements and textual notes around work is tremendously useful as an exercise for thinking the work through. And also: I also remain aware of the ways that the professionalization of a practice is also often detrimental to one’s imagination and creative intuition, particularly at a practice’s most vulnerable points. Many of my readers are in Houston and I have watched these past couple of years as galleries there are starting to reach out to artists just completing MFA’s (or my beloved Block program) in town, developing exhibitions/sales based around the (irritably patronizing) discovery of these artists who, of course, have been there all along.

This move coincides with the difficulties of the pandemic, of shipping delays, of increased costs: I understand these things. And yet, I see so many emerging artists, hungry for exhibitions, bend into the forms of what they think is desired by these spaces: again, I understand. And then I watch artists competing amongst their communities for these spots, presenting very polished and tedious work that sidesteps experimentation in favor of local accolades, gallery shows, juried awards, and every other kind of boring CV addition you can imagine. But the world is burning, my loves, and your CV isn’t going to change that.

In resistance toward the ways such opportunities mold us into their preferred forms, what I’m suggesting for this week is: write some concrete poetry. Break your statement into fragments and rearrange them into an image. Fracture the sounds inside your sentences into howls and gurglings and stutters and exclamations. Make new sounds, away from meaning. Remember that words are materials, too. And, as materials, they can also be decoupled from their relationships to specific logics and systems. Make letters and their weirdnesses your visual material for a moment. Make words your allies, your informants, your unpredictable cousins, your colorful flotsam, swaying and gathering alongside the other things you make in your studio. Make a mess of them, sound their sounds toward the new moon, accumulate piles of them in a corner of your studio, stick them on walls in public spaces, find the word-sounds that wake your dog from a nap, juggle them into sentences that stretch for days and lead nowhere. And, once you’re comfortable in their insistent unpredictable wordy chaos, let’s see what they might bring into your studio work…

This, then, is a prompt for letting that statement goooooooo.

A book for you.

In line with this week’s prompt, I’ve been reading Gal Beckerman’s book The Quiet Before: On the Unexpected Origins of Radical Ideas. In short, narrative case studies that span many countries over hundreds of years, Beckerman considers the ways in which forms of communication (letter-writing, charter-signing, manifesto-proclaiming) have offered space for humans to find solidarities with one another. And, in turn, these solidarities, Beckerman argues, eventually lead to worlds changing. By researching that quietness before revolution, Beckerman pushes against the distractions of immediacy, insisting that the ways we use language to connect to one another are ultimately as urgent and worth protecting as the subsequent flares of protest and conflict. In fact, I think he would argue, that these quiet moments give a depth and clarity to protest that assures its impact.

Some videos for you.

Last fall, I developed a three-part series of lunchtime talks around the question of how to interview artists and work with the interview as a material for scholarship, curatorial work, and historical revision. I met with Josh Franco from the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian, Arden Decker from the International Center for the Arts of the Americas at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and Nichole Christian whose decades of arts journalism have been foundational for developing an art history of Detroit. All three conversations are now available to watch on Vimeo. You can find them, here: Josh Franco, Arden Decker, Nichole Christian.

Laura August, PhD makes essays and exhibitions, lumpy pots and wild gardens. She has curated more than 20 exhibitions as an independent curator working between the U.S. and Central America. In 2021, she was named an inaugural Mellon Arts + Practitioner Fellow at the Yale Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity, and Transnational Migration, and her writing about contemporary art in Guatemala City has been recognized with an Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant. Alongside her consulting practice for artists and writers, she teaches a process, practice, and professional strategies class for artists at the Glassell School of Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. She currently makes her home on the edge of the Chihuahua Desert, and she is Curator at the Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts at The University of Texas at El Paso.